The Veterinarians’ Guide to Your Cat’s Symptoms: care of an injured or sick cat

When a pet cat is injured an owner often must make some immediate decisions about what to do and how to do it. If a cat is ill or recuperating from surgery or injury, the owner must be prepared to look after him and tend to his needs, which may include giving medications and caring for bandages. In the case of a chronic illness such as diabetes mellitus or other long-term problem, an owner may be called on to medicate a cat for the rest of the animal’s life. In this chapter we will include a brief rundown of some of the more commonly occurring emergency and recuperative situations and how to deal with them.

Emergency First Aid Steps Most injuries and serious illnesses require immediate veterinary care as we pointed out in Chapter 4. It is a waste of precious time for an owner to attempt first aid steps that may do moreharm than good in the end. However, there are certainly situations in which something must be done to make a cat more comfortable and, perhaps, to save his life, especially in the case of traumatic injury. An owner must attempt to stop serious bleeding, and an injured cat must be transported to the veterinary office or emergency clinic in a way that will do him no further harm.

Handle With Care!

A severely injured cat is likely to be in pain and will also be badly frightened. An owner should realize that the first thing an injured cat will try to do is run away and hide, so she must be prepared to secure the cat right away. If he is too badly injured to run off, he may strike out at anyone, even his owner, when he is approached or touched. Anyone attempting to minister to an injured cat should protect her arms and hands as well as possible, and should avoid putting her face near the cat’s.

As we mentioned in Chapter 2, some sort of secure carrying case should be a standard piece of equipment for all cats. If there is no carrying case available to put an injured cat in, the best way to secure the cat and prevent being scratched is to wrap him, securely but gently, in a towel, small blanket, sweater, or other piece of clothing. Wrap his body and legs, leaving his head out. He can then be placed in a carton or box, or someone’s lap, and held while being transported to the veterinarian. It is best to helper’sassisitance, because even a badly injured cat may be able to work his awayhis way out of a wrap and injure himself further.

Stoping bleeding We discussed the use of a pressure bandage, and how to apply one, in Chapter 4. In the case of spurting, arterial bleeding it may be necessary to apply manual pressure with a clean cloth or bandage placed on top of the wound to stop the flow of blood; then a pressure bandage can be applied. As we stated in Chapter 4, we do not advocate the use of tourniquets because they can easily cause permanent limb or extremity damage.

Resuscitation If a cat is not breathing (apnea), or his heart is not beating (this can be readily ascertained by feeling the chest area for a heartbeat), immediate must be taken to avoid brain damage. If the cause is electrocution from biting a pluggedin electric wire, be sure the wire is unplugged before touching the cat. It is rare for a cat to drown, but cats can stop breathing due to smoke inhalation or a chest wound.

It is important to note here that, in a case of full-blown cardiac arrest, even the best-equipped intensive care facilities in major veterinary hospitals with expert staff have only a 4 percent rate of success in resuscitating cats. Therefore, the chances of an owner being able to successfully resuscitate a cat with cardiac arrest are very slim. Most owners, however, feel they must try.

Artificial Respiration The easiest way to perform artificial respiration to start a cat breathing again is by mouth-tonose resuscitation. The cat’s mouth should be sealed tightly closed using two hands, then the person’s mouth should be placed firmly around the cat’s nose. With gentle blowing into the nose for several seconds eight to ten times per minute, the cat may be encouraged to breathe on his own. Once the cat has begun to breathe he should be taken to the veterinarian right away.

CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION (CPR)

If a cat has stopped breathing and his heart is not beating, he may be helped by CPR, a combination of heart massage and artificial respiration. As we pointed out above, however, this procedure is hardly ever successful.

The cat should be put on his side on a hard surface. His airways should be cleared by pulling out his tongue and checking inside his mouth and throat before beginning. First, mouth-tonose resuscitation should be performed. If there is still no heartbeat, heart massage can be performed. A cat’s heart is located just behind his front legs. With gentle pressure, the heel of a hand should compress the cat’s chest and then release it in a regular rhythm. This should be repeated about six to ten times, then mouth-tonose resuscitation repeated. If no pulse is felt, the process may be repeated, but if no positive results are seen after approximately ten minutes, the process is probably in vain. The best course to take is to have someone try to obtain veterinary help, or drive to the veterinarian with the cat while the resuscitation effort is under way. As an alternative to laying a cat down and using the heel of the hand, a person can grasp a cat’s chest behind the front legs with the thumb on one side and finger on the other side. The chest can be compressed rhythmically during transportation.

Home Care of a Sick or Recuperating Cat Inexperienced cat owners, in particular, are often very concerned about their ability to take care of or medicate a sick or recuperating cat. Some cats are extremely difficult to medicate, and even the best-natured cat requiring regular medication will quickly learn to run off and hide as soon as he sees or smells the medicine. An owner will soon know if this is the case with a particular cat and should confine the cat in one room (preferably one with few pieces of large furniture to get under, such as a kitchen or bathroom) well before the medication needs to be given.

If a cat simply cannot be medicated at home, the veterinarian may be able to help. Sometimes, a different form of medicine may be easier for an owner to use, or a cat may have to be taken to the doctor’s office in order to be medicated.

Restraints and Tricks It is always easier to medicate or treat a cat when he is up on a counter or tabletop. It is also preferable to have a helper who can stand behind the animal and hold him while he is being treated. To give oral medication or treat a cat’s head or mouth, the helper can hold the cat in her arms, grasping his front legs so he cannot scratch. Many cats become very frightened when they are restrained too firmly A good-natured cat, placed on a counter or tabletop, may only require gentle holding while he is medicated.

If a procedure is painful or unpleasant, or if a cat is very panicky or aggressive, more serious restraint may be needed. A cat that is frightened or aggressive will probably strike out, so owner and helper should protect their arms and hands before attempting treatment or medication. One good way to restrain a cat that needs only his head or one paw or leg treated is to wrap his whole body in a towel. Gently shaking a cat by the loose skin at the back of his neck will often distract him sufficiently to perform a quick procedure on his body. Another way to keep a cat quiet for an examination or brief procedis to have a helper stretch the cat out to his full length on his side on a counter or tabletop by holding his neck and back legs.

If it is still impossible for an owner to medicate or treat a cat at home, he may have to be hospitalized and tranquilized for treatment. A cat that immediately tries to lick off any ointment or salve, chew off a bandage, or scratch his head or ears, for instance, may need to wear an Elizabethan collar for a while. This is a soft plastic cone, available from a veterinarian, that ties or snaps around the animal’s neck behind his ears and extends beyond the tip of his nose so that he cannot get his mouth to any part of his body or scratch any part of his head or ears (see illustration). Cats hate these devices but they are sometimes necessary on a temporary basis. The collar must be removed at intervals, under strict supervision in a closed room, to allow the cat to groom himself, eat, and drink. Do not allow the cat to escape. It will be very difficult to locate and recollar him if you do!

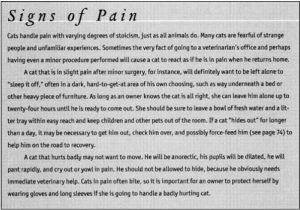

General Daily Care of a Sick Cat A cat that is sick or recuperating from an operation or accident is in a somewhat fragile condition. That is, he is apt to be more sensitive to extremes of temperature, and more bothered by loud noise and commotion. Just as with a human patient, a cat that doesn’t feel well should be kept warm and protected from roughhousing children and other pets. Many cats really want to be left alone when they are not well; others crave loving attention from their owners, or from one special owner. An owner should take her cue from her pet in this regard.

Most cats have one or more favorite sleeping places and should be allowed to have the run of the house so they can choose where to sleep. An owner must be sure the cat is warm enough wherever he sleeps; an extra blanket, or even a heat lamp above the cat’s sleeping area, may be needed if the house is cool. If a cat persists in hiding underneath a heavy piece of furniture, he must be removed from time to time, forcibly if necessary, so he can be given food and fluids. If a sick or recuperating cat is unable or unwilling to venture out of a room in the house, he must have a litter tray, food, and water nearby.

An owner may be asked by the veterinarian to take the cat’s temperature on a regular basis. The veterinarian should demonstrate how to do this, but basically, a helper is recommended. Cat’s anal-rectal muscles are very strong and it may be difficult to slip a thermometer in.

The cat should be placed on a counter or tabletop. A rectal thermometer lubricated with vaseline or mineral oil should be used, shaken down, and inserted until only about one inch is visible. It should remain in place for one minute. A normal temperature for a cat is about 100 to 102.5 degrees Fahrenheit.

Cats often become anorexic when they are ill. This is especially true if their sense of smell has been affected. Sometimes, very strongsmelling fishy food will encourage a cat to begin to eat again. If this doesn’t work it may be necessary to force-feed a cat. Nutrients in paste form, such as strained baby food that does not contain onion powder, can be placed on a fingertip and wiped directly onto the roof of a cat’s mouth. Alternately, liquid nutrients can be placed in a large dropper or syringe, available from a veterinarian or pharmacist.

Tilting the cat’s head upward, pull his cheek out gently to form a funnellike opening into which the liquid can be squeezed. It will trickle into the animal’s mouth through his teeth.

Water should be given in the same manner.

Medicating a Cat

As we mentioned above, medicating even the best-tempered cat can be very difficult, even for experienced cat owners. Three basic rules apply for successfully giving oral medication to a cat: learn to anticipate a cat’s attempts to escape; get help when needed; stay calm; and be patient.

Because cats are such good escape artists and seem to be able to know way in advance when a medication is going to be given, the primary rule is to confine a cat well ahead of time.

Liquid medicine is the easiest to administer to many cats. As with forcing liquids above, hold the cat close to the body and tilt the cat’s head back. Hold the cat’s mouth closed and insert the dropper or syringe tip in the side of the mouth in the cheek pouch. Administer the medicine in this pouch and it will run through the teeth into the mouth. If the mouth is held closed it will make it difficult for the cat to spit out the medicine. Unfortunately, many liquid medicines are elixirs (alcohol- based), which cats do not like. Others are flavored for humans, especially children, and have fruit flavors that cat palates do not appreciate. Some pharmicies will compound liquid medicines in catfriendly flavors such as fish or chicken.

Pills and capsules cannot be hidden in food for cats as they can for dogs; cats will simply spit them out. Pilling a cat usually requires a second person to hold the cat from behind to keep him from backing up.

With some cats, wrapping them up in a blanket or towel can replace the helper. The person administering the pill should grab the cat’s head with the palm of the hand over the nose, thumb on one side of the upper jaw and index finger on the other side (see illustration, right). Tilt the cat’s head back and open the mouth with the other hand by pressing down on the lower jaw as the top jaw is squeezed with the first hand. The pill is then inserted over the tongue and toward the back of the throat (see illustration, above right). It should be given a quick push over the hump of the tongue and the mouth quickly closed. Then blow gently on the cat’s face and massage his throat, which will encourage him to swallow.

This difficult process does improve with practice.

Eye medicine comes in two basic forms, liquid drops and ointment. In either case, it is important not to poke or scratch the cornea with the applicator tip. The cat must be held still (helper or blanket wrap) and the medicine should be placed in the corner of the eye nearest the nose.

This is where the third eyelid is and this organ helps protect the cornea from the applicator tip. It also helps to rest the hand holding the applicator on the top of the cat’s head to steady it (see illustration, above). The medicine can then be placed in the lower eyelid. After applying the medicine, close the eyelids so the medicine will be distributed over the entire eye.

Ear medicine is usually fairly easy to apply to a cat, unless his ears are very sore or tender. It also comes in liquid or ointment form. Hold the cat’s head steady with one hand, place the applicator directly into the ear canal, and squeeze. It is not necessary to stick the tip all the way into the ear. Then massage the area beneath the ear to spread the medicine into the ear canal, which runs down the side of a cat’s head.

Skin ointments and salves are easy to apply. The trick is to keep a cat from immediately licking them off. Sometimes a distraction such as a delicious meal, favorite toy, or gentle brushing may distract the cat long enough for the medicine to work (approximately ten to fifteen minutes).

If a cat cannot be distracted and it is very important for the medication to remain on his skin, an Elizabethan collar (illustration, above) may be necessary, especially at night when no one is watching the cat.

If a cat requires injections at home, the veterinarian will demonstrate how to give them. Sometimes medicated baths art prescribed, especially for skin conditions. Follow the instructions for bathing a cat in Chapter 2.

If it is impossible for an owner to treat a cat at home, the cat may need to be hospitalized. Casts and Bandages Casts and bandages are usually left alone between veterinary visits.

The hardest job for an owner is to keep them dry and as clean as possible, especially if a cat is allowed outdoors. It is usually not a good idea to allow a cat free range outdoors if he is wearing a cast or large bandage because his mobility will be affected and he will be unable to escape from dogs or other cats.

If a cat persistently chews or scratches a bandage or cast, or constantly licks the area around it, it may be necessary to use an Elizabethan collar (left) to prevent soreness and infection from developing. If an owner notices a bad smell or any swelling, irritation, or redness around a cast or bandage or in any part of a bandaged limb, such as a paw, the veterinarian should be contacted immediately. Most bandages or casts will leave toes exposed at the bottom of the bandage. An owner should check the toes often (several times a day) to see if the toes are swollen.

Any swelling of the toes should be checked by a veterinarian; it usually indicates a bandage or cast that is too tight or has slipped, interfering with circulation to the lower limb.