The Classic Comprehensive Handbook of Cat Care: PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Physical examination consists of applying knowledge of anatomy to a routine and thorough inspection of all or part of your cat’s body. Each person (including every veterinarian) develops his or her own method for giving a physical examination. The best routine to develop is one that prevents you from forgetting to examine any part and one with which you feel most comfortable.

Example: Examine your cat by systems as set out in this chapter (muscle and bone, digestive system, etc.) Then return to examine miscellaneous items such as eyes, ears, and lymph nodes. Then take the cat’s temperature.

Example: Take the cat’s temperature. Proceed with examination starting with the head and working toward the tail. In addition to examining special structures in the area—e.g., ears, eyes, mouth, and nose for the head, claws and pads for the limbs—don’t forget to examine the skin in each area and to look for the lymph nodes associated with each area. Follow up by watching your cat in motion.

Special tools needed for physical examination: A rectal thermometer is the only special tool necessary for performing a routine physical examination of your cat at home. Your other tools are your five senses, particularly the senses of touch, sight, and smell.

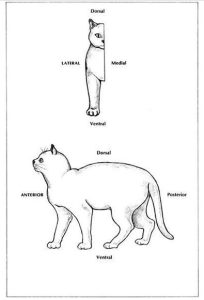

Special terms used in physical examination: Except for anatomical names of body parts that are mentioned and illustrated in this chapter, there are few special terms that you need to learn to help you with a physical examination. Refer to this page if any of the following words are confusing in the text.

Palpate—to examine with your hands. This is one of your most important methods of physical examination and is why you are asked to palpate or feel parts of your cat’s body so frequently throughout this book.

Terms which indicate direction in reference to the body are illustrated on the facing page.

You can do a better job of giving your cat health care at home with some basic knowledge of anatomy and physiology. Anatomy is the study of your cat’s body structure and the relationship among its parts. For example, knowing the location of your cat’s eyes and ears and their normal appearance is knowing anatomy. Physiology is the study of how the parts of your cat’s body function. Understanding how your cat’s eyes and ears function to enable your cat to see and hear are examples of understanding physiology. Although you will be able to examine and understand anatomy easily, physiology is much more difficult. Brief descriptions of how your cat’s various body parts work are given here, but it takes intensive study, such as that your veterinarian has given the subject, to really understand physiology well.

You will be most concerned with the external anatomy of your cat, but some internal anatomy is included as well, since an introduction to it will help you understand your veterinarian more easily as you discuss health problems your cat may have. The easiest and fastest way for you to become familiar with what you need to know is to get together with your cat and the following pages of this book. Handle your cat as you read the anatomical descriptions and look at the drawings. If you have a kitten, examine him or her several times during growth. You will see many changes over several months, and the physical contact will bring you emotionally closer to one another.

Looking carefully at your cat’s anatomy and encouraging your cat to sit quietly while he or she is examined are extremely important in preparing both yourself and your cat for times when you will have to give health care at home. Also, the maneuvers you go through in examining your cat at home are the same ones your veterinarian uses when giving your cat a physical examination. A cat who has become accustomed to such handling at home is usually more relaxed and cooperative at the veterinary office.

Place your cat on a smooth-surfaced table in good light for examination. The smooth surface prevents good traction and, therefore, a “quick getaway,” and the novelty (at least for some cats) of being on a table will entice many cats to stay put rather than attempt an escape. Use a gentle touch and a minimum of restraint. Most cats respond poorly to heavy restraint: A hand placed gently over or in front of the shoulders or under the chest is usually sufficient. If your cat squirms and tries to get away, interrupt the exam, lift the cat quickly off his or her feet while voicing the command “No!” firmly, then replace the cat on the table. Don’t give up. Although cats don’t seem to be as naturally inclined to respond to obedience training as dogs, they can and do learn to respond to your wishes if you make them known clearly and you are consistent. Be sure to praise your cat whenever he or she cooperates, and repeat the correction procedure wherever he or she tries to escape.

The best procedure for a very uncooperative cat is to start out with very short exam periods, repeated frequently. As the cat becomes accustomed to the procedure and reassured that no injury is going to occur, cooperation improves and the examination time can be increased. There are several methods of firm restraint to use with cats, but these should be reserved for use in the veterinarian’s office or when you have to administer “disagreeable” treatment to your cat. Rely on consistent repetition and gentle handling to establish a good working relationship with your cat.